Understanding the Defense Retirement Reforms in the Bipartisan Budget Act

As CRFB has explained in a recent analysis, the Bipartisan Budget Act under consideration in the Senate would replace a portion of the mindless sequester cuts with more targeted reforms. One controversial proposal in the bill would reduce cost-of-living adjustments for working-age military retirees. This blog explains that provision.

In broad terms, the Bipartisan Budget Act would use $85 billion of targeted deficit reduction to pay for almost $63 billion of defense- and non-defense sequester relief. As a result, the $20 billion defense cut which would occur in mid-January is replaced with a small increase.

The military retirement provision in particular would reduce COLAs by 1 percent (but not to below 0) for working-age pensioners below 62 (many of whom work in second careers), with a one-time catch-up at 62 so that retirees above age 62 are held completely harmless. This provision would save $6 billion in mandatory spending, but by reducing the amount the Department of Defense has to fund their pension accounts, actually allows $8 billion more in defense spending.

In other words, the savings from the military retirement provisions are not actually going toward deficit reduction, but instead toward funding other defense needs. The Pentagon can make much-needed reductions to its compensation costs and free up resources to build an adaptive 21st Century military.

Understanding Military Retirement Benefits

Currently, members of the military become eligible for retirement benefits after 20 years of service. As a result, many start receiving retirement benefits as early as their late 30s, and on average begin collecting by age 42. For 20 years of service, benefit levels generally equal half of a beneficiaries' highest 3 years of work, and 2.5 percent more for each additional year worked beyond 20. Benefits then grow every year with the Consumer Price Index.

The fact that members of the military can retire so young has important implications. For one, most retirees have second careers while collecting their pensions – sometimes as civilian employees at DoD, sometimes as military contractors for high profile companies, and sometimes in fields completely unrelated to their military service.

It also means that a military retiree is likely to spend more time collecting retirement than serving in the military; an officer who serves for 20 years beginning at age 22 and then lives to the average male life expectancy of 82 will have collected 40 years of retirement benefits for 20 years of service. In the private sector and civilian workforce, the opposite tends to be true – most Americans spend closer to 40 years working to collect 20 years of retirement benefits.

Why Is Military Retirement In Need Of Reform?

According to the Defense Business Board, military retirees eligible for pensions receive a benefit more than 10 times greater than private sector equivalents. Although there is good reason to provide generous benefits for those who serve in the military, many defense experts and officials worry this level of benefits is ultimately unsustainable.

According to Defense Secretary Gates in 2010, "Health-care costs are eating the Defense Department alive, rising from $19 billion a decade ago to roughly $50 billion." Current Secretary Hagel said “Without serious attempts to achieve significant savings in this area, which consumes roughly now half the DOD budget and increases every year, we risk becoming an unbalanced force, one that is well-compensated but poorly trained and equipped, with limited readiness and capability.”

Although health benefits are a big part of this, funding retirement benefits cost about $16 billion per year – which is about 34 cents for each dollar of basic pay for active duty personnel. The cost of military benefits is growing over time, while sequestration means that the total money available is shrinking. The chart below shows the amount of each service member's total compensation package (including health and retirement costs), which has grown faster than inflation.

Source: CBO

In addition to funding concerns, the current military retirement system is in many ways broken. As a Moment of Truth Project paper explained in 2011, those with 19 years of service get nothing while those with 20 years walk away with one of the most generous pensions in the country. This creates bad incentives, including by encouraging skilled members of the military to exit shortly after their 20th year, but also creates questions of fairness.

How Does the Bipartisan Budget Act Change Military Benefits?

Although fundamental reform is ultimately needed, the Bipartisan Budget Act makes only a modest change to military retirement benefits – temporarily reducing COLAs for those below the age of 62. This means that instead of receiving 2.3 percent benefit increases in a typical year, working-age military retirees would receive 1.3 percent. In years inflation is higher they would receive more, but in no case could their increase fall below 0. This policy is far more modest than the recommendation of the Bowles-Simpson Fiscal Commission, which recommended completely eliminating COLAs for retirees under age 62.

Yet like the Fiscal Commission recommendations, this policy would provide a one-time "catch-up" in pension levels at age 62 (to what they otherwise would have been), and then grow benefits with CPI after that. This means that there is no change to pensions for beneficiaries older than age 62 either now or in the future.

Some critics have argued that this modest change would reduce the lifetime value of pensions by more than $80,000. Although their figures are accurate, critics fail to put the number in context of an average lifetime benefits for enlisted personnel of $2.4 million. In other words, the total reduction, relative to current law, would be about 4 percent of cash pensions (forgetting health and other benefits) – and this would come when most retirees are working elsewhere and earning supplemental income.

In addition to saving money and enabling more targeted spending on defense programs, reducing COLAs until age 62 could also help encourage longer careers in the military and help retain experienced military officers. The reduced COLA would still leave military pensions better protected from inflation than most of those in the private-sector.

Finally, it is important to understand where this money would go. As we've explained before, the Bipartisan Budget Act provides over $22 billion of sequester relief on the defense side – meaning defense spending will be $22 billion higher than under current law. But the $6 billion of savings from this provision would allow DoD to contribute $8 billion less to the Military Retirement Fund to cover future pensions, thus providing an additional $8 billion, beyond the $22 billion, to put toward military readiness and other defense priorities.

How Does This Proposal Affect the REDUX Retirement System?

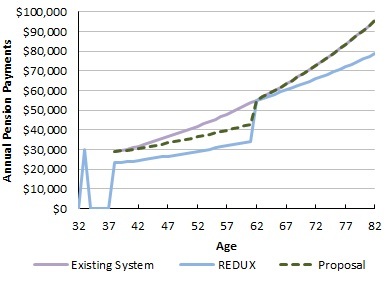

Currently, service members can choose from two retirement systems – the High-36 system we described above, or an alternative system called REDUX. Although most choose the traditional system, those choosing REDUX receive a one-time $30,000 payment in exchange for accepting initial benefits that are 10 percent lower and a COLA of CPI minus 1 percent. This proposal would not change REDUX at all, and thus might make it somewhat more attractive to servicemembers.

Pension Payments of a Typical Military Retiree Under Three Systems

Source: CRFB staff calculations based on a service member who retired in 2013 at age 38 with an E-8 rank (Sergeant First Class). Salary information from the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Conclusion

There is broad recognition, from Chairman Ryan to Defense Secretary Hagel to Army Chief of Staff Ray Odierno, on the need to reform military compensation. The changes to military pensions in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 is a modest step in that direction, slowing the growth of one of the nation's most generous retirement systems for those not yet of retirement age.

These changes come with a cost – lifetime benefits will be 4 percent lower, on average, than they otherwise would have been. But these reforms are part of a package with substantial benefits. This package avoids immediate cuts in defense spending, provides relief to the mindless non-defense discretionary cuts, frees up further resources for military readiness, and reduces the deficit by more than $100 billion over the next two decades.